Ultra-Wideband Localization

Introduction

There are numerous industries that are in the process of developing autonomous passenger vehicles. Such vehicles have the capacity to reduce risk and free time of riders. In the development of an autonomous vehicles, a key consideration is reliable localization in order to plan for and react to the environment. Typically,h igh position accuracy is achieved through the use of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS). The use of GNSS with an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) or odometry measurements can lead to an accurate positioning system.

Reliable GNSS measurements are often not available. Because GNSS receivers must have line of sight with at least four satellites, environments that include obstructions pose significant challenges. Urban canyons, tunnels, or indoor environments degrade or fully obstruct GNSS signals, forcing the system to rely on dead reckoning. These measurements are subject to drift, and therefore cannot be trusted after continued interruption of GNSS. As such, it would be advantageous to the continued development of autonomous vehicles to use a exteroceptive sensor for navigation through environments where GNSS is typically denied.

Ultra-Wideband (UWB) radio, utilizes low-energy pulse communication typically for short-range, high-bandwidth applications. By measuring time of flight across various frequencies, it is possible to measure distance between modules while overcoming multipath errors. This has allowed UWB modules to be applied towards localization and tracking problems. With the continued development of UWB technology and roll out in commercial products, it’s ability to aid in navigation should continue to be explored.

By using UWB ranging, autonomous vehicles can generate ranging estimates to other independent vehicles. Just like measurements to landmarks, these measurements are not subject to drift when GNSS measurements are obscured, and can be made available in both indoor and outdoor environments. Known as collaborative localization, these measurements can leverage the growing number of intelligent vehicles on the road, and can increase the accessible area of autonomous vehicles.

Background

Ultra-Wideband, with it’s previously mentioned benefits, is a very promising technology for localization. There are many examples of using UWB ranging modules for high-accuracy indoor localization of ground or aerial systems. These systems typically measure with respect to fixed landmark anchors.

There are also examples of using UWB modules for outdoor vehicular environments. Such a framework has the capacity to increase localization accuracy of existing systems, or provide accurate localization in environments where GNSS is not reliable, such as tunnels or urban canyons.

Given a network of vehicles, it is possible to leverage relative measurements to provide better localization accuracy as a group, than as a collection of individuals, generally referred to as collaborative localization (CL). These methods are generally classified in two groups: centralized methods, and decentralized methods.

Centralized CL

Centralized CL methods use a single or multiple fusion centers, to which every vehicle communicates measurement information. These state estimators are capable of producing optimal linearized state estimates and have been used in a number of applications with success. A major issue with centralized networks is sensitivity to failure. As the number of measurements made can increase on the order of O(n^2), centralized networks can meet constraints when large networks of nodes are implemented with complex measurements or update functions.

Decentralized CL

Decentralized CL (DCL) methods are defined by distributing the state estimation computation across every agent in the network. Unlike centralized methods, DCL methods are not susceptible to single point failures. These generic, recursive approximations of the centralized method can extend the framework to decrease convergence time or computational cost without loss of accuracy.

Contributions

This research seeks to expand upon previous work through the following contributions

- Expanded previous UWB EKF and DCL simulation environments through the incorporation of vehicle and sensor models and the framework for Monte Carlo simulations.

- Validated the zero-mean normally distributed error assumption for a UWB ranging module.

- Showed EKF localization improvements using real-time UWB measurements to landmarks in GNSS denied environments.

- Showed DCL accuracy improvements by utilizing real-time UWB relative ranging measurements.

Decentralized Collaborative Localization

The decentralized collaborative localization algorithm is a form of a Kalman filter that approximates the centralized filter through distributed computation. The estimation of the entire state of a network is broken down into smaller filters where each vehicle has private controls and measurements that are used internally and relative measurements that require the sharing of state and covariance information.

For a network of N vehicles, each vehicle initializes its own 6-DOF state and assumes zero cross-correlations between the vehicles until a relative measurement is made. As such, the number of vehicles does not need to be known.

Initialization

It is assumed that at the beginning of any network, the vehicles positions are uncorrelated. Therefore, the network state can be initialized with the initial beliefs of each vehicle and the cross correlation is set as a zero matrix.

When the vehicles come into sensing range, generally the cross correlation is no longer equal to zero and therefore the cross-correlation term can be decomposed to allow each vehicle to maintain estimates of cross correlation terms that can be combined at the next relative measurement. The decomposition sets the cross-correlation of the sensing vehicle equal to the true cross-correlation and the sensed vehicle estimate equal to the identity matrix.

Control

It is assumed that the vehicles follow the motion model g(U) where control input U is an IMU measurement. The prediction step for a vehicle is given by the standard EKF equations.

Private Update

It is assumed that the private update measurements are functions of the state of a single vehicle with a Gaussian error disturbance h(x). These updates come from GNSS positioning and UWB landmark ranging measurements.

Relative Update

It is assumed that the relative update measurement to be a function of the state of two vehicles with a Gaussian error disturbance. These updates come from vehicle-to-vehicle relative UWB ranging measurements. The cross-correlation estimates are combined to be used in the best state estimate of the approximated system.

Simulation

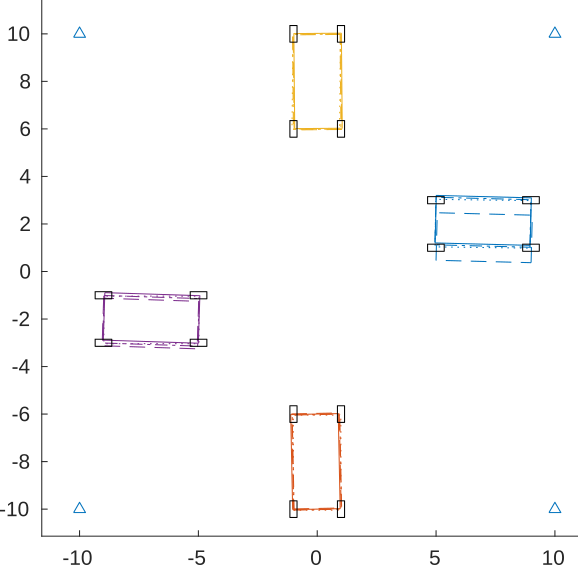

In order to simulate various collaborative localization algorithms, a simulation framework that would be flexible in number of cars and networking was created in MatLab: collab_localization repository. The simulation was designed to handle an indeterminate number of cars and configurations. Additionally, to facilitate the testing of collaborative localization, UWB tags can be treated as either fixed landmarks or mobile units on other vehicles.

Sensing Models

The UWB sensing model was implemented with Gaussian normal randomly distributed errors with a measured standard deviation of 0.31 meters.

The GNSS sensing model takes a Circular Error Probable (CEP) error value and converts into a distance root mean square (DRMS), which is approximately 84.93\% of CEP. This DRMS value is input to a circularly symmetric Rayleigh distribution to perturb the measurement.

Output

The resulting output of this software package is a visual animation of the simulation, position error summaries for each vehicle, and the final state and covariance. When compiled in Monte Carlo simulations, these data can be used to evaluate filter performance improvements.

Results

Using the simulation framework, it was possible to test a wide variety of vehicle environments and sensor configurations. These configurations included vehicles moving parallel to each other, vehicles moving perpendicular in street crossings, and moving in groups in tunnels without GNSS measurements. Additionally, UWB landmarks were added to each of these situations.

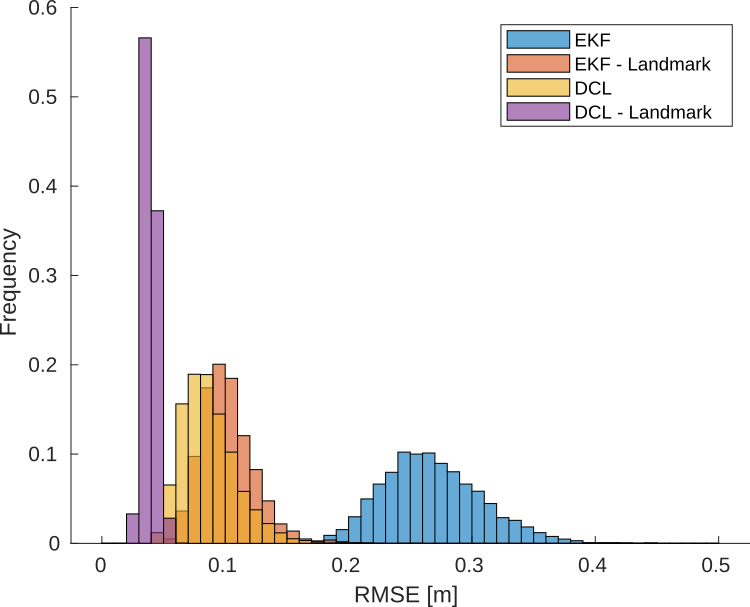

Examples of the Monte Carlo simulations performed are shown. These figures show the crossing of two vehicles at an intersection using various estimation algorithms.

The simulations showed that UWB measurements offered improvements to localization accuracy across all experiments. Using more vehicles improved accuracy, and using additional landmarks offered significant improvements. This was especially the case in situations where GNSS data was not available such as tunnels and urban canyons.

Experimentation

The filter framework was tested in Bryan, Texas using the Unmanned Systems Lab autonomous trolley. The Decwave EVK1000 evaluation boards were mounted alongside a VectorNav VN-300 and ArduSimple RTK GNSS. The trolley itself includes PACMod, a by-wire kit prepared by Autonomous Stuff, which gives access to wheel odometry and steering data.

Using tripods, a second set of UWB ranging modules were placed in various experimental setups to either represent road landmarks, or a second vehicle.

As in the simulations, the addition of the two UWB sensors on the vehicle offered improvements to the localization accuracy of the vehicle in all scenarios. The improvement was even more pronounced when GNSS data to the VN-300 was denied. The quality of data coming from the VN-300 was underestimated, leading to much higher location accuracy than simulated. As such, the percent improvement from simply adding UWB measurements was lower than in the simulations, with the smallest percent improvement being 2.9% and the largest being 9.3%. However, removing the GNSS updates showed results much more in line with the simulation, with the addition of UWB measurements showing a 83.3% improvement in localization accuracy in a tunnel environment.

Future Work

Future work for this reserach includes

- Experiemnts with additional tags and multiple moving vehicles

- Explore transitional space between GPS and GPS-denied environments

- Compare the decentralized approximation to the centralized method

- Simulate the effects of delays in the system

In the future, testing will include more in-person experiments with multiple moving vehicles and a greater number of UWB tags. This would allow for better evaluation of truly cooperative localization using of vehicles using UWB and will validate the algorithm used in simulation. This will also explore the use of real-time varying covariance estimations in the update equations.

Preprint

A preprint of the paper can be found here.

@INPROCEEDINGS{9564981,

author={Hartzer, Jacob and Saripalli, Srikanth},

booktitle={2021 IEEE International Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC)},

title={Vehicular Teamwork: Collaborative localization of Autonomous Vehicles},

year={2021},

pages={1077-1082},

doi={10.1109/ITSC48978.2021.9564981}}

Related Works

- L. Yao, Y. A. Wu, L. Yao, and Z. Z. Liao, “An integrated IMU and UWB sensor based indoor positioning system,” in 2017 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), pp. 1–8, 2017.

- L. Luft, T. Schubert, S. I. Roumeliotis, and W. Burgard, “Recursive decentralized localization for multi-robot systems with asynchronous pairwise communication,” The International Journal of Robotics Research, vol. 37, no. 10, pp. 1152–1167, 2018.

- S. I. Roumeliotis and G. A. Bekey, “Distributed multirobot localization,”IEEE Transactionson Robotics and Automation, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 781–795, 2002

- S. Tanwar and G. Gao, “Decentralized collaborative localization with deep gps coupling for UAVs,” in 2018 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium, PLANS 2018 - Proceedings, (United States), pp. 767–774, June 2018.